Wolves: Shape-shifters in a Changing World, a new exhibition at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, shines a light on one of nature’s most misunderstood creatures.

Just think about it. Many fairy tales, books and movies give wolves a bad rap. The Big Bad Wolf is the main villain in both The Three Little Pigs and Little Red Riding Hood, as well as the 2022 animated movie Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the wolf Maugrim is in charge of the White Witch’s secret police. And in Sergei Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, the titular canine is captured for the crime of eating a duck, then carted off to a zoo.

(Of course, it hasn’t been all bad news for wolves in pop culture, particularly in recent decades. One wolf even befriended Kevin Costner in Dances With Wolves.)

The Museum of Nature show includes a small section devoted to the often-unfair portrayal of wolves in popular culture, but it covers a lot more ground than that.

The show’s starting point: Stunning wolf photography

Ottawa-based wildlife photographer Michelle Valberg planted the seed for the exhibition when she approached the museum with an idea. She had recently created some breathtaking images of wolves along the coast of British Columbia and in Yellowstone National Park in the United States. Would the museum be interested in displaying them? The answer was yes.

Valberg chose 11 striking photographs, along with commentary and context. A panel next to her photo Alpha notes of its subject, “He approached us at the shoreline, stared at us and then began to howl—clearly showing that he was the boss.”

To capture these images, Valberg spent days on end hidden in blinds. Her patience was rewarded with unforgettable scenes, such as wolves reuniting with their pack, feasting on a whale that had washed ashore or simply sunning themselves.

The photographs were printed on metal using a process called ChromaLuxe, which results in large, luminous, detailed images. Honestly, it feels like some of the wolves are about to walk right into the museum’s gallery.

The images were “the starting point of the exhibit,” says Nicole Dupuis, an exhibition content developer at the museum who pulled Wolves together. “But of course, at the museum, we also have research and collections—and we have quite a strong collection of wolf material.”

Delving into wolf science

“Strong” is a bit of an understatement. The Canadian Museum of Nature actually holds one of North America’s largest collections of wolf-related items, numbering some 2,500 specimens.

Using a tiny number of those items, the exhibition explains the basics of the museum’s research in easy-to-understand language. For instance, museum palaeontologist Dr. Danielle Fraser has hypothesized that wolves survived the last ice age—when many other large mammals did not—by changing what they ate.

Displays show how wolves have evolved with different coats, different skills and different sizes to adapt to a huge range of environments. In fact, they are now the most widely distributed land mammal. “They can live in forests, they can live…along the coasts, in prairies and deserts,” says Dupuis. “They’re very agile at changing their behaviour.”

A large display in the middle of the gallery invites you to use all your senses to find out more about wolves. Shift the lid of a silvery cylinder and sniff, and you might catch the scent of a deer—something wolves can detect from over two kilometres away. On the display, you can pet a soft square of wolf fur—but don’t reach out to pet the wolf in the display. If you try, you’ll trigger an audio alarm—the low rumble of a wolf growling. (I learned this first-hand, because I’m not the sharpest museum visitor in the drawer.)

In case you’re wondering where the museum acquires its specimens, don’t worry—researchers don’t hunt wolves. Dupuis explains that many recent additions to the collection are, sadly, wolves who have been struck and killed by cars.

Indigenous perspectives on wolves

In the show, you can learn about an ongoing project led by the Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, Magnetawan First Nation, Shawanaga First Nation on Manitoulin Island, in collaboration with researchers from the University of Guelph. Together, they are blending Western and Indigenous knowledge and techniques to study wolves in the Georgian Bay area. By finding out where the wolves live, how they’re doing and how they’re adapting, the researchers hope to support wolf conservation efforts.

In many Indigenous cultures, wolves are seen as strong, loyal and courageous. These traits are vivid in three artworks in the exhibition—a wolf painted on a paddle by Dean Ottawa, an artist from Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation; a silkscreen print of a man morphing into a wolf by Art Thompson, a Nuu-chah-nulth artist from the Ditidaht First Nation, and a stone-cut print by Quvianaqtuk Pudlat, an Inuit artist from Kinngait.

On a video playing nearby, Cree Elder Wilfred Buck tells the story of the “dog stars” (a constellation also known as the Little Dipper). In the story, wolves, coyotes and foxes realize humans need helpmates and companions. They become dogs to keep humans company and help them hunt, carry heavy loads and protect their settlements from predators.

From wolves to dogs

Another section of the exhibition explains how wolves evolved into dogs. Researchers don’t agree on when exactly when that happened; it could have been over 20,000 years ago. However, most experts concur that our association with dogs is the oldest sustained human-animal relationship (it likely began long before the domestication of farm animals and, yes, even cats).

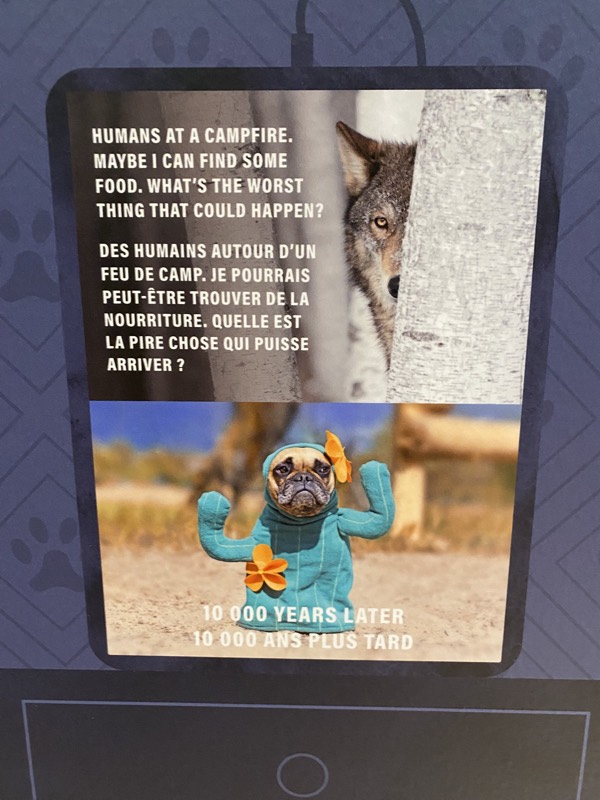

One of the panels in this section truly made me laugh out loud:

On display are the skull of an early dog, as well as specimens from three modern species: a St. Bernard, and English bulldog and a chihuahua. Together, they make the adaptability of wolves (and their dog descendants) pretty easy to visualize.

P.S.: If you’re a dog lover, you can submit photos of your pet for possible inclusion on the museum’s website and in the exhibition. (Cleverly, the project is called “Wolf to Woof.” Search the hashtag #WolfToWoof on social media to find adorable dog photos galore.)

The future of wolves

Many people hope that wolves’ legendary adaptability will help them survive the climate change crisis. After all, they made it through the ice age when many of their mammal contemporaries did not.

The last section of the show looks at current population numbers and the future of wolves. The exhibition’s take? Wolves are resourceful at adapting and surviving, but some help from us—in the form of efforts to rein in climate change and preserve habitats—certainly couldn’t hurt.

If you go

Wolves: Shape-shifters in a Changing World is scheduled to run at the Canadian Museum of Nature (240 McLeod Street, Ottawa) until March 18, 2024. You’ll find the exhibition in a gallery on the third floor. Admission to the show is included with general admission to the museum. See the museum’s website for more information.

P.S.: For the two weeks spanning Quebec’s and Ontario’s March Breaks, there will be hands-on wolf-themed activities for kids in the exhibition gallery.

Looking for more tips on things to see and do in and around Ottawa? Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter or order a copy of my book, Ottawa Road Trips: Your 100-km Getaway Guide.

As the owner of Ottawa Road Trips, I acknowledge that I live on, work in and travel through the unceded, unsurrendered territory of the Algonquin Anishinaabeg Nation. I am grateful to have the opportunity to be present on this land. Ottawa Road Trips supports Water First, a non-profit organization that helps address water challenges in Indigenous communities in Canada through education, training and meaningful collaboration.

1 comment

[…] Posts Learn fascinating facts about wolves at new museum… 50+ fun things to do in March, in… 25+ ideas for March Break in Ottawa, the… Lofts du […]